The last couple of months have been quite stressful. Strangely enough, I have found the ultimate relief in early Almodóvar films.

“Almodóvar?” you ask. “Isn’t that the director who makes those flamboyant, disturbing Spanish movies with Antonio Banderas or Penelope Cruz? How can those be stress relief?”

I respond to your rhetorical question with another one posed by A.O. Scott:

“Can there be such a thing as exuberant melancholy?”

No, seriously – Tony’s question is a valid one with regard to Almodóvar’s films. How can he make movies that breathe so well – that can be funny, disturbing and tragic all at the same time without resorting to recognizable clichés? Whether or not one buys into the auteur theory, Almodóvar has an unmistakable directorial signature that nevertheless produces a very different film every time. To quote Tony again, “[his] plots thicken and explode according to their own peculiar logic.” (Which is why I’m s0 excited about I’m So Excited.)

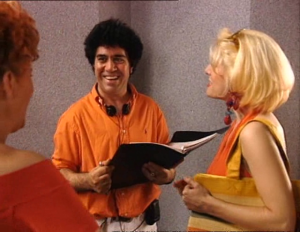

Kika is an uneven, postmodern, self-conscious mess with spectacular pacing and characterization. The film is about an upbeat protagonist in a vicious, cruel society full of the depraved and the depressed, much like in Mike Leigh’s Happy Go Lucky (2008). It has all the trappings of a dark comedy, but Almodóvar (as with many of his early comedies) reaches for the bottom of the abyss.

SPOILERS FROM HERE ON DOWN

The titular protagonist is a make-up artist who gets involved in affairs with a voyeuristic photographer and his writer/serial killer father Nicholas. The apex of the film occurs when the voyeur son Ramón films from a distant apartment as Kika is raped three times by a randy prison escapee, all whilst Ramón’s father murders a woman in the bedroom upstairs. While any other film would frame this moment in the most misogynistic terms imaginable – emphasizing the voyeuristic affinities between the spectator and the three male perpetrators – Almodóvar manages to play the scene for laughs (i.e., the rapist convict lasts for a ridiculously long time), and our sympathies never stray from Kika and her companions.

And so I got to thinking about HBO comedies and all this long-form television that people so hungrily consume these days… and how all of it could be so much darker and sympathetic toward women, if only Almodóvar were at the helm. Discussions of Bertolt Brecht recall how good the director was at drawing connections between material conditions and the agency of those characters who must endure them. Almodóvar outclasses Brecht by finding endless labyrinths of desire within both the society and characters who maneuver within it, such that we are constantly transitioning between ironic and melodramatic registers in a fashion pleasurable to the astute viewer.

I don’t think it’s on Netflix (OK, it’s on Hulu Plus.) But it’s a gem worth seeking for its total reconfiguration of genre, expectation, and gendered expectations of narrative. An invasive-but-friendly brain massage.

In an age that continuously exalts novelty, I’m suddenly excited to re-watch all the titles from the 1980s and 90s that I seem to have curiously missed.

Posted by guyintheblackhat

Posted by guyintheblackhat